In Jewish culture, the Ketubah stands out as one of the oldest and most prevalent documents associated with marriage. Originally serving as a contract unrelated to religious beliefs, similar to other documents of its time, it involved only the elders of the family in its preparation and execution.

According to written references, Ketubah ceremonies have been conducted for generations, held during special gatherings among family and acquaintances, and often in the presence of esteemed community elders. These joyous celebrations end as the bride enters the groom’s chamber.

Following the construction of Solomon’s Temple (the First Temple), the Ketubah’s content underwent a transformation, influenced by the religious and legal developments of the time. Jewish scholars understood the importance of creating a legal basis for marriage encompassing the responsibilities and entitlements of both individuals involved. The legal provisions were established by referencing the laws in the scriptures and following Halachic rules. This process gained speed during Israel’s exile when scholars worked to finalize the Ketubah text.

As the Jewish community spread to various locations, the Ketubah document went through modifications in its design. According to tradition, the twelve tribes descended from the sons of Jacob had individual Ketubahs dedicated to themselves around 1200 BC. These Ketubahs were uniquely identified with their ancestors’ names or symbolic images. For example, the tribe of Judah’s symbol was a lion, based on the blessing given by Jacob to Judah, while the tribe of Issachar was represented by the sun. Other tribes had their own associated symbols.

The oldest discovered Ketubah belongs to Egypt and dates back to 440 BC. It was written in Aramaic on papyrus. The content of this Ketubah indicates the agreement between the groom and the bride’s father regarding the bride’s dowry, emphasizes the bride’s position as his wife, and her rights and entitlements in case of the husband’s death, where she legally becomes the owner of his property.

Over time, as Jews migrated to far-off places, the Ketubah became an important document for a shared life. The woman in the family was entrusted with its safekeeping until she passed away. Once the parents died, it was passed on to their children as a tradition to preserve their names.

It is worth mentioning that all the changes made to the original format of Ketubah were influenced by the customs of Jewish communities in those regions, taking into account the cultural and artistic conditions of the time and place. These changes were primarily aimed at beautification and optimization, without fundamentally altering its written nature. In other words, the continuity of Ketubah until today is due to the sacredness of the text.

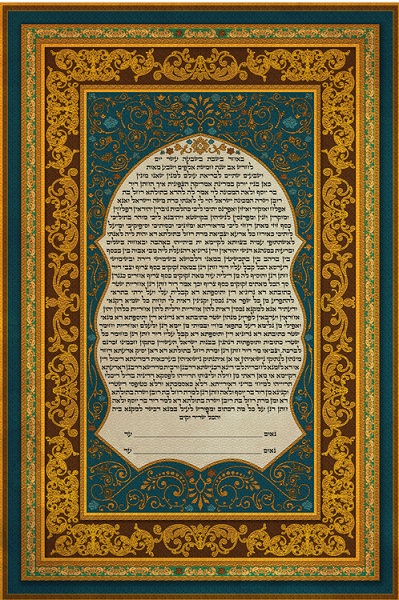

As previously mentioned, all the alterations in the visual appearance of Ketubah were mainly for decorative and aesthetic purposes. Writing Torah verses and using colorful images such as flowers, nightingales, birds, heavenly fruits like apples, pomegranates, grapes, and images of sacred items like the shofar, menorah, Star of David, and also creations of God (i.e. nature) like the sun and the moon, all demonstrate cultural and historical beliefs.

Over time, some of these changes were influenced by the art of non-Jewish ethnic groups, especially in Islamic countries and European countries under the Ottoman Empire’s rule in the 18th century.

The influence of Islamic arts in Iran on Ketubah can be observed from the beginning of the Safavid rule. The beautiful designs, along with Hebrew and Persian calligraphy and even the use of Arabic letters (in the Ketubahs of Jews in Mashhad in the 19th century), are prominent examples of the impact of Islamic art and the skill and taste of Iranian artists in creating Ketubahs throughout these centuries.

Before the invention of printing, all the artistic creations and writings in Ketubah were done by painters and calligraphers. Later, they also used wooden stamps with various designs, composite motifs, plant-based colors, and even gilding to simplify and expedite the process. Gradually, parchment was replaced with paper, with high-quality paper more commonly used.

As printing became more widespread, a sense of consistency in how Ketubahs looked and were designed started to take shape. They were typically made in two sizes, with some being around 50*35 centimeters (considered large) and others around 36*15 centimeters. However, it is important to remember that personal preferences played a role in determining the dimensions of some Ketubahs. These standardized dimensions led to organized Ketubah ceremonies and wedding celebrations. Moreover, adhering to the legal requirements of the country where the bride and groom resided became necessary for Ketubahs.

It is worth noting that in Iran, traditional handcrafted Ketubahs were more common than printed Ketubahs until the beginning of World War II.

According to some reports, printed Ketubahs were brought to Iran in the 1930s from the Holy Land for the first time by Mashhadi Jews. The Mashhadi Jews were also the first to use these Ketubahs. The text in these Ketubahs was entirely Hebrew. Soon, various printed Ketubahs were also brought by pilgrims to Tehran and other cities across Iran, quickly gaining popularity and becoming widely adopted.

With the advancements in printing technology, particularly in the West, the Ketubah underwent a remarkable transformation in appearance from the late 20th century onward. Hundreds of diverse Ketubah designs resembling beautiful paintings were created, printed, and reproduced by artists, giving couples a wide array of options for their wedding contracts.

Old Ketubahs in Iran are mostly related to the Qajar era, which were often single-paged documents made of paper with dimensions of 70*50, 60*40, or 35*20 centimeters, or booklets with dimensions of 30*15 or 22*10 centimeters, containing either four or five pages. Both types of Ketubahs featured paintings and calligraphy.

One-page Ketubahs were more common in central cities of Iran. In addition to calligraphy on all four sides and decoration with vibrant colors, these Ketubahs were sometimes gilded using gold or silver too, and included decorated verses from the holy scriptures in large Hebrew letters. The use of gold leaf for gilding was another distinguishing feature between Isfahan Ketubahs and those from other cities.

Among the distinctive designs of Ketubahs in Iran was the use of carpet or rug patterns. However, Ketubahs featuring carpet designs varied from one city to another, with Mashhad’s Ketubahs being different from Yazd’s or Shiraz’s, for instance. The carpet patterns used in Ketubahs were symmetrical and appeared as a border surrounding the document, just like a rug. Cities such as Mashhad, Hamedan, Kermanshah, and Khansar were among those that integrated the rug patterns more prominently in their Ketubahs. The design’s uniformity allowed them to use ready-made wooden or leather stamps (usually with three or four stamps), ink, and colors like red, brown, and green for painting flowers, vases, and birds.

Sources used:

Mythical Beliefs: Yusef Setareshenas