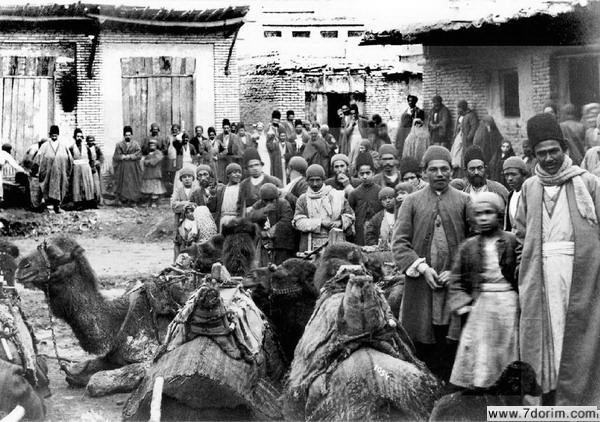

Odlajan neighborhood and Hafet Kenisa alley

Photo from the archive of Habib Levy Cultural Foundation

Mr. Kohanka and Dr. Shorovich in the main square of Odlajan neighborhood in 1339

Photo from the archive of Alliance School

Mr. Kohanka and Dr. Shorovich in the main square of Odlajan neighborhood in 1339

Photo from the archive of Alliance School

The entrance side of Odlajan from the south side (15 Khordad)

The title “Kalimi” is used solely to refer to Iranian Jews. It comes from the word “Kalim”, in “Kalim Allah” (i.e. the one who speaks with God), which was Moses’ title, since he was the Jewish prophet.

Jews play an integral part in the history of Iran, however, the history of Iranian Jews remains relatively under-documented. The available documents consist mainly of recollections of past events, often highlighting misfortunes. Additionally, reports from European Jewish travelers and organizations offer summaries of population statistics and religious perspectives. Even so, even these writings testify to the active presence and shared existence of the Jews with their fellow countrymen in Iran, which was sometimes challenging and distressing.

A glimpse into the past reveals that the central nucleus and population of the Jews of Iran resided in more or less segregated neighborhoods. These neighborhoods, in addition to communal living, also accommodated synagogues and catered to their religious requirements. It goes without saying that these neighborhoods bore no resemblance to the ghettos of Europe. In Isfahan, the most renowned of these neighborhoods was the Joubareh neighborhood and in Shiraz the periphery of the Gowd Arban district. In other cities, Jewish neighborhoods existed in proportion to the population, the most significant of which was the Jewish neighborhood of Tehran, known as ”Oudlajan”.

The Oudlajan neighborhood, one of Tehran’s five ancient districts on the outskirts of the market, is bordered by Mowlavi Square to the south, Amir Kabir Street and Sar Cheshmeh to the north, Shams Ol-Emareh to the west, and Imamzadeh Yahya to the east. On Tehran’s oldest maps, a section of Oudlajan is identified as the “Kalimi” area. The Kalimis referred to this part as “Sarchal” (Sar + Chal), which likely derived its name from being a passageway to another old neighborhood, ”Chal-e Meidan”. “Sar” means “beginning of” and you would have to first pass Sarchal to reach Chal-e Meidan. Over time, the Jewish-inhabited sector of Oudlajan became known as “the neighborhood” or “Sarchal” by Muslims and Jews, a designation that endures today.

Another narration suggests that there was a pit in the central square of the Jewish neighborhood, where rainwater and wastewater from the alleyways would drain into this pit and well. Since “Chal” means “pit”, this place was consequently dubbed “place of the pit” or “Sarchal”.

From the Qajar era (1794-1925 AD) when Tehran was divided into distinct neighborhoods, each neighborhood demonstrated unique characteristics and conditions. The residents of each neighborhood could be recognized by the name of their neighborhood. Tehran’s Jews were referred to as “Sarchal people,” and the inhabitants and merchants of this neighborhood were primarily Jewish. Of course, Muslims also resided in the neighborhood. However, the territory of “the neighborhood” was the sole location where Jews constituted a majority and, in a sense, exercised an unannounced administration.

In those years, the population of the Jews of the neighborhood was estimated to be around twenty thousand people. They resided in the central area of the neighborhood or the surrounding alleys. Following the 1940s, however, as Tehran expanded, the Jews of Tehran also gradually relocated to various parts of the city.

After the migration, the number of Jewish residents of the neighborhood decreased day by day. Nonetheless, the interaction between Muslims and Jews in the neighborhood always demonstrated the valuable understanding between Iranian-Islamic and Iranian-Jewish cultures. For example, although Muslims and Jews had a strong adherence to their religious beliefs, each side considered itself bound to respect the beliefs of the other side. Jews participated in Muslim mourning ceremonies, and in some cases they themselves organized such gatherings. And Muslims did not disturb Jewish religious duties.

Although the Jews of the neighborhood were still subject to attacks by Muslims from time to time, but these attacks were organized by individuals outside the neighborhood who were usually professional thugs and extortionists. These attacks caused physical, spiritual, and financial damage to the Jewish families.

The small geography of the neighborhood held fourteen synagogues and two mosques within itself. Sometimes, the call to prayer of Muslim worshipers from the mosques mixed with the sound of Jewish religious songs in the synagogues, but it was rarely ever a cause of protest or an obstacle to the fulfillment of religious obligations for either side.

Describing or even imagining the current state of the neighborhood is difficult nowadays. City renovations and development have transformed the neighborhood, leaving no future for what used to exist. The population is now a mix of marginalized individuals and a few Jewish and Muslim families. Life in the neighborhood is temporary and precarious, and fewer and fewer of its former residents care to explore its streets today.

The only remnants of the neighborhood’s Jewish past are the three synagogues that are kept alive by worshipers who visit from other neighborhoods and uphold their daily prayers there. Another remaining relic is the Dr. Sapir Hospital. Survived thanks to the tireless efforts of the Tehran Jewish Committee and charitable individuals, this hospital stands as a testament to the neighborhood’s enduring spirit. It stands as a tall symbol of hope.

Nothing is strange about this neighborhood — neither its delusional past, nor its collapsing present. Everything is happening as it should. These old buildings, with crumbling walls, the repulsive smell of poverty that lingers in the air, and the determined fate of the people make it clear that everything has changed and will continue to change. The buildings have changed, the streets have changed, and the people have changed too, but nothing has improved, nothing has become more beautiful. Although nothing beautiful existed here in the past either.

The aging houses, often constructed below street level for water storage, now stand as echoes of the past. The narrow alleys, characterized by low and dark ceilings recite the tales of historic fears. They all seem to be taking their final breaths. Today, a different group, facing even greater impoverishment than before, temporarily occupies these spaces. These dimly lit houses, however, connect to broader streets where people sell various goods in a handful of somewhat decorated and posh shops. It appears that life flows for these people like a river — everything that has been determined to happen, will happen.

Nowadays, the majority of the neighborhood’s residents are Afghan Muslims. However, in the past, Jewish shopkeepers played a vital role in fulfilling the neighborhood’s needs. The local businesses included butcher shops, kosher eateries, groceries offering kosher cheese produced within the neighborhood, and stores specializing in religious supplies. These merchants, along with itinerant cloth vendors selling their goods outside the neighborhood shaped the economic landscape of the area.

Moreover, the neighborhood had a few candle-making and weaving workshops run by Jewish men in the blacksmiths’ market. Additionally, the clinics of a couple of doctors, midwives, and teachers from the Alliance schools acted as vital links between the neighborhood and the wider community. The wealthier individuals in the neighborhood were essentially the owners of various textile shops in the Tehran Bazaar, particularly in the cloth market.

That said, there is a major difference between the neighborhood today and what it used to be. That difference is the intimacy of the people. The people were closer to each other, the harmony between them was better, the mixture of children playing and laughing amid the market buzz and the ceaseless movement of residents blended into a harmonious symphony that was unique to the neighborhood, composed here and belonged to it. At night, this song found another allure with the uniform sound of the beehive lights of the shops and their distinct illumination.

In the neighborhood, it only took one seasonal rain to turn the dirt on the ground into muddy swamps. As pedestrians passed with shoes that were made specially for such days, they would often amuse themselves by splattering each other with mud as they made their way through — a game they had accepted as part of their life.

Back in the day, the neighborhood was filled with men rushing to make it to the synagogue for their daily prayers, while some calmly walked, busy with their thoughts. Meanwhile women who were always looking for a cheaper price, rushed home to prepare lunch for the family with a basket under their colorful chadors. And then there was the children who contributed to the neighborhood’s life — they had to go to school reluctantly, only to come back in the afternoon tired and worn out. These everyday scenes were the rhythm of life in the neighborhood, and they shaped the character of the place. Today, the neighborhood is quieter, but its essence remains intact. The people who live there have adapted to the changes, and the neighborhood carries on, its history etched in its very bones.

Young people sought to develop a business for themselves in order to prove their maturity and ensure an income for their future — for their marriages, which had been arranged before. Their primary focus was learning as little Hebrew as necessary for reading the Torah, the Psalms, the prayers, and the religious scripts in their synagogue. They learned Hebrew at home or at the synagogue, and to them, the ability to repeat these religious texts was something they would be proud in, something that demonstrated their honor.

Young men and women who were to marry each other typically knew one another well. Marriages were held with utmost simplicity and ease. The concept of love and romance rarely crossed their minds. The only thing they knew about love was the familiar story of Zuleikha and Joseph — a story devoid of the passionate prelude associated with modern love and with an ending that was not romance. If the parents ever did find the time to tell their children stories, they would be stories of suffering and pain rather than love and happiness.

Just like the narrow asphalted streets of the neighborhood, the manners of the people there have changed too, as if a bulldozer has ruined the people’s values just like it demolished the houses. Traces of Jewish heritage have vanished from the neighborhood. A single family resides in the Ezra Jacob synagogue, along with two other ladies, and a man and his son. Meanwhile the Hadash Synagogue operates on Saturdays under the guidance of an enthusiastic elder and his friends. The Molla Hanina Synagogue is maintained by members who live outside the neighborhood. An elderly man, reminiscent of homeless individuals in Iran and America, stands as a visible reminder of Jewish presence in the Sarchal neighborhood. He is the only person who announces his Jewish identity to the people of the neighborhood every day, earning acceptance and help from the residents and merchants

Taken from the book The Sixty-Year History of the Jews of Iran written by Harun Yeshayai, 2011

Detailed map of Sirus Three Roads and Serchal neighborhood and Odlajan neighborhood (click on the photo to see more details)

Approximate map of the area of Yehudiyan neighborhood in Tehran, drawn by engineer Jahangir Benayan (1321) taken from the archive of engineer Aziz Banayan

Oudlajan neighborhood – west side of Sirus Street, Takiyeh Reza Qoli Khan

Reza Qoli Khan neighborhood on the west side of Sirus Street, Takieh Reza Qoli Khan Koy leading to Oudlajan

Takiyeh Reza Qoli Khan

Takiyeh Reza Qoli Khan KoiyI: narrow and narrow alleys left over from the architecture of the last century

The door of the house with a male knocker on the right and a female knocker on the left

Oudlajan Tekyeh Reza Qoli Khan Koy Sangi

East side of Siros Street, formerly Sarjambek (Taqavi)

A path of piety leading to Emam Zadeh Yahya

Northeast side of Koy Emamzadeh Yahya neighborhood

Southeast side – Emamzadeh Yahya

Eastern side – Koy Taqavi

Koi Taqowi intersection of Koche Alavi

Eastern side of the neighborhood – Koy Mirza Mahmoud vazir

The eastern side of the headrest of the throne, the Saqakhane of the throne

Ezat al-Doleh Street

Since Naser al-Din Shah’s time, Oudlajan was considered a noble Qajari neighborhood where many of the nobles of Qajar lived. The word Oudlajan or Oudlajlar comes from the word “Oud” and “Laji”, referring to the apothecary market there.

Agha Aziz dead end

Eastern side of the neighborhood – Mirza Ali Asgar bath (special for Muslims), a bath building in the style of past baths, about 10 meters below the street level.

Mirza Ali Asgar bath entrance

The interior view of the bathroom (in the architectural style of the bathroom belonging to the Qajar era) is one of the bathrooms left over from the past

Bathroom dressing area

Corridor leading to private bathroom

The east side of Siros Street, Mast Bandan

Mastbandan Street, East Side

As for the textile area of the neighborhood; the name makes it clear that in this area, most shops focused on textiles, although there was this one shop that sold yarn, spools, ribbons, and laces in various colors and widths. That store belonged to Yahuda Kashi and his son, and the store was called Aflak (i.e. the heavens). There were also a few liquor stores and one tailor. Itinerant cloth merchants bought supplies from these shops and subsequently sold them in Muslim neighborhoods and villages surrounding Tehran. They often carried the cloth bundles themselves, occasionally relying on thin and frail donkeys too.

Adapted from Jahangir Banayan’s Note

Koy Sar Jambek (Taqvi) in Masjed Alley

End of Masjid street on the East Side

The first time Tehran’s map was crafted was about 150 years ago. The Austrian teacher of history, geography, arithmetic, geometry, and artillery techniques at Darolfonoon School, August Karel Kříž, was tasked to craft a detailed map of Tehran. He created a comprehensive map, detailing the passages, alleys, and significant structures. The structure of Oudlajan and the list of its residents reveals it was inhabited by Qajar nobles, court members, officials, ambassadors, and Christian and Jewish minorities during the Qajar era. Such nobles existed in each part of the historical area of Oudlajan. Unfortunately, some historical buildings have succumbed to neglect and urban development by the Tehran municipality.

A house in Koi Masjed remains of the past civilization

Replacing the new buildings and the dying civilization of the last century

A mosque that is more than a century old in the mosque alley on the eastern side

East Side Tagavi Alley

Alley in front of Abolghasem Shirazi Alley

Taqavi Alley – Abolghasem Shirazi Alley

East side of Siros St. – Sorsori Alley

A combination of new and old architecture:

West side of Siros street – Masjed Hoz alley, Left side

Shop and house of Dawood vegetable seller

Masjed Hoz alley, leading to Oudlajan neighborhood

West Side of Cyrus Street of the Oudlajan Neighborhood

Haim David Anary’s shop sold Faloodeh (a traditional Persian cold dessert) and ice cream in the summers. In winter, they sold Fereni (Persian pudding made from milk, starch, and sugar), offering them in small bowls that people could eat from in front of the shop. This stretch also included a liquor store, Moshe Khodadad’s butcher shop, Molla Haim and Son’s Tripe shop, Ebrahim Aush Kashki’s Aush-e Kashk shop (an Iranian thick soup made with Kashk cheese), and finally Shimoun Poost-Tarash’s Sheepskin shop. He handled sheepskins from the slaughterhouse or in the market, separating wool with his specialized tools.

A traditional Iranian marketplace featured Yaghoub Ghahvechi’s small coffee shop. The coffee shop offered tea during the day and meals like rice with carrots and beans (similar to Mexican rice) or rice with meat stew for lunch, which people could also take away. This was the only restaurant from noon onwards since the tripe, Haleem stew, lentils, and Aush-e Kashk shops served food in the mornings. This restaurant did not have tables or chairs, so people would either have to take their food away, or sit somewhere on the ground and have their lunch.

West side of Siros Street, Odlajan neighborhood

Odlajan neighborhood – Kashfi alley

West side of Siros Street, Odlajan neighborhood

Oudlajan Street

The registered historical landmarks of Oudlajan include Khan Marvi Mosque, Farmanfarma’s House, Hakim Mosque’s cistern, Imamzadeh Yahya’s shrine, Russian Embassy Garden, Naib al-Saltana Bazaar, Printing House Building, Hakimbashi Bathhouse, Khanom Bathhouse, Qavam al-Dawla’s House, the Friday Prayer’s Imam House, Sar Cheshmeh Water Shrine (Saqqakhaneh), Motamen Ol-Atebba’s House, Shahi Mosque and Bazaar, Khan Marvi School, Pamenar Mosque and Minaret, Rezaieh School, Vossug’s House, and Mirza Mahmoud Mosque. Regrettably, this historically rich Oudlajan neighborhood, listed as an eternal national monument, is being demolished by the municipality, raising concerns amidst the silence of the authorities of the Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handcrafts and Tourism Organization.

Serchal alley leading to Serchal neighborhood

Mashallah Yazdi, the only survivor of a Jewish tradesman in Odlajan alley

Mashallah Yazdi with more than 65 years of residence in Odlajan neighborhood

Winter 2009

-Sarchal Street-A house previously owned by Rahmat Shams (Mashhadi) and Musa Morghi. They had over 10 families as tenants in this house.

A house previously owned by Rahmat Shams (Mashhadi) and Musa Morghi. They had over 10 families as tenants in this house.

Near the Sarchal bathhouse, a small synagogue and several residences were situated, including the house of Mr. Aghajan Esfandi, known as Aghajan Lakhti, who sold tonbaks (goblet drums). On the west side of Sarchal, there was a metalworking shop and another butcher shop. Moving towards the southern side, besides Davood Anari’s shop, there was a butcher named Abanani (Kadkhodazadeh). Abanani specialized in purchasing Sangak bread (stone-baked bread) from Muslim bakeries and selling it to the residents of Sarchal.

Sarchal was also home to a few Jewish musicians or singers, who had their unique way of communicating. Their musical skills were often passed down through generations, with boys learning the art from their fathers. They taught each other various instruments, including drums and violins. This hereditary practice played a crucial role in preserving Persian music, especially considering its prohibition in Islam. It could be concluded, therefore, that Persian music survived after the Arab conquest of Iran only because of the Jews, because music was forbidden in Islam. Jews have a great share in preserving and promoting Persian music.

Serchal area, the area of Kuche Haft Kenisa, part of which has been turned into a park

A view of the remains of the Haft Synagogue Alley

Haft Kanisa street (i.e. Seven Synagogues street). A remaining synagogue that has been converted into a residential house.

All synagogues were cleaned from a few days before Yom Kippur. The carpets were washed, and most synagogues were painted. Everything had its designated place so that on the night of Yom Kippur, with the light of candles and lanterns, there was a special atmosphere, especially since everyone, young and old, tried to wear their cleanest clothes. In short, the appearance of the night of Yom Kippur in synagogues had a different charm.

Western side of the Seven Synagogues neighborhood.

Around twenty large and small synagogues are visible in the small area of Oudlajan. Between Sarchal and our house, there was a synagogue called Hakim Synagogue, which had a room on the east side. In this room, Mr. Mirza Falgir (father of Jamsheed Keshvari) was busy with fortune-telling. His room was always full of Muslim, Armenian, and even European customers who came to him for fortune-telling. Below this room, there was a water storage tank, which unfortunately was not very large, and it had a gutter with steps. Those who did not have a water storage tank in their homes used this water tank.

Excerpts from Jahangir Banayan’s notes.

The entrance door of the synagogue (former)

Sarchal alley and the lanes around it were full of Jewish houses, synagogues, and shops. People of this neighborhood had created a friendly atmosphere, and everyone knew each other. This community had a significant role in preserving and promoting Iranian music, especially during the Islamic period when music was considered forbidden.

Excerpts from Jahangir Banayan’s notes.

The western side of the neighborhood (Oudlajan) is one of the alleys of the former Jewish settlement, which was located at the end of Faloodeh Shirazi’s shop alley.

West side of the neighborhood – Borazjan Alley

Borazjan Alley – the location of Halots, the first youth cultural center in the neighborhood

A Narrow Alley in Sarchal

Located in Tehran during a time without pipe water, this narrow alley was home to a small stream that flowed past each house with a cistern or pool. The stream’s current would carry water into the cisterns, but often, these holes would accumulate mud and worms, making the water less than desirable for household use. Furthermore, the unpaved alleys were always covered in dirt and filth, and during rainy periods, this debris would be led into the stream, and as a result, mix with the water in the cisterns.

Sarchal Neighborhood

Talking of Sarchal square, did you think I am talking of a grand plaza like Tupkhane Square, Fuzieh Square, or 24th Esfand Square? Far from that, the houses and narrow alleys of the neighborhood were so tightly packed that the square, a meager 100 square meters in area, appeared more like a small patch of open space. To add to the image, this little patch was almost always filled with garbage. If it wasn’t for the farmers from around Tehran who sometimes used this garbage as fertilizers, no other person or organization would clean that mess.

Eastern Side of Sarchal Neighborhood

The small Sarchal Square stood at a lower latitude than the streets around. No wonder it was called Sarchal (i.e. Top of the pit). All that was needed was a rainfall to bring all the dirt of the mountains around right into Sarchal Square, turning it into a little pond. However, safely crossing the eastern side of this little pond to the western side was impossible. For that, you would have to pass by bulging eyes of dead cats and dogs with opened mouths, as if to tease you.

Small butcher shops added to the neighborhood’s unique ecosystem by dumping excess meat scraps onto their rooftops. This provided a haven for a multitude of cats and dogs who gathered and roamed the interconnected rooftops at night.

Oudelajan – Kuche Sanegi – Kuche Hakim – leading to Ezra Yaqoub Synagogue

An Alley Next to the Ezra Yaghoub Synagogue

The house where I was born in was situated approximately 25 feet from Sarchal, itself a small neighborhood within Oudlajan district. Oudlajan was one of Tehran’s five most prominent neighborhoods, and Sarchal was known for its narrow streets and small square. Put together, it was considered by the people as a neighborhood of its own. My childhood home consisted of two rooms, a small courtyard, a cistern, and a covered corridor. The covered corridor was only a meter high, which meant that the grownups always had to lean when they wanted to pass through this corridor to exit or enter the house. Otherwise their heads would hit the roof.

Adapted from the writings of Jahangir Banayan

Eastern Side of Sarchal Alley Leading to Oudlajan

Shmuel the grocer had a shop on the northern side of this alley, while Zion the barber’s shop was a bit to the east. I went to Zion’s barbershop once, but Zion wouldn’t cut my hair himself because I wasn’t a grown up yet. That would be the job of his apprentice, who, instead of using a shaving machine, opted to pluck my hair one by one, much like pulling a nail out of wood. The dull razor caused excruciating pain, prompting me to save myself from the apprentice by leaving a hundred dinars on the counter and fleeing.

The east side of Siros street, theParvareshghahalley

The orphanage building of Iranian Jewish Women Organization has been evacuated for some time

Part of the destroyed areas in Odlajan

Spring 2009